Akka Work Pulling Pattern to prevent mailbox overflow, throttle and distribute work

Update June 2015

This post is about two years old now - please consider it only as nice reading material to learn about distributed work patterns. The presented implementation has a number of edge cases that the post does not deal with. While it’s possible to handle them, I would not suggest doing so. For a real world use case I would rather use a reactive streams implementation for it.

Work Pulling Pattern

I just gave a talk about the Work Pulling Pattern at NY-Scala (slides), so I figured it’s a good time to update my previous article on the Work Pulling Pattern. It’s based on Derek Wyatt’s blog post who should get all credit for it - I’ve just picked it up and explain it in isolation.

This pattern ensures that your mailboxes don’t overflow if creating work is fast than actually doing it - which can lead to out of memory errors when the mailboxes eventually become too full. It also let’s you distribute work around your cluster, scale dynamically scale and is completely non-blocking. At work we use it in a number of places, and Victor Klang and Ronald Kuhn from the core Akka team told me that they use it aswell - that should be reason enough to have it in your toolbox.

Scenario

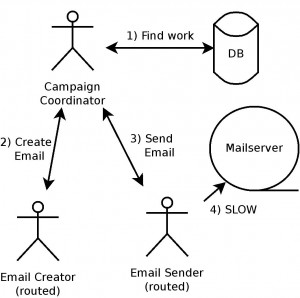

Let’s assume we want to send out a couple of million emails. (No, I’m not talking about spam, but newsletters that people want!). We have an email template which is the same for everyone, and recipient-specific context with information like name, email address etc which we fetch from some database. The Campaign Coordinator fetches those contexts and we call that our unit of work. Even if there’s only one single Campaign Coordinator, this part of the process will be really fast. A second actor called Email Creator is responsible for assembling the actual email from the template and the context. And finally the Email Sender actor is sending it out to a mailserver, which is rather slow in comparison as it involves network traffic to some other machine.

A naive implementation with actors could look something like this: the receive loop of the Campaign Coordinator handles a Go message which make’s it fetch a batch of work (e.g. 1000 contact informations). It then sends each work individually to the Email Creator and pipes the response (the final email) to the Email Sender. If we found some contacts, chances are there’s more available, so we call ourself recursively in the end. By working with batches we ensure that the Campaign Coordinator has the chance to receive other messages during the execution, e.g. if we want to stop it.

case Go ⇒

val batch = findWorkBatch()

batch foreach { work ⇒ emailCreator ? work pipeTo emailSender }

if (batch.size > 0) self ! Go

Note that emailCreate ? work runs in a separate Future and does not block - check out the ask pattern if you’re not yet familiar with it. You probably figured the problem yourself by now: the Campaign Coordinator is really fast and enqueues heaps of messages in the other actors’ mailboxes, which are slower, so they accumulate lots of work over time. Specifically the Email Sender’s mailbox will quickly grow, as it’s the slowest part in this process. Even if we use routed actors to send out the email (which we should anyway!) - we have no guarantee that producing the work isn’t still faster.

A few 'solutions' with caveats

A few ideas that first came to our mind when we run into this. They all have caveats and I’ll explain why: 1) Configure a high number of Email Senders so that it’s not that slow any more. Problem: the number of parallel execution is limited by your dispatcher, which is typically using as many concurrent threads as the number of CPUs available. Also: what’s a good number and how do you figure that out? 2) Use bounded mailbox sizes for the slower actors, so that the work-producing actor cannot persist any more messages. Problem: it blocks the producing actor, so we loose one execution thread. More importantly, it behaves differently if the receiving Actor is not on the local node but somewhere else in the cluster: in that case the message gets delivered to the dead letter queue. 3) Derek Wyatt’s PressureQueue. It’s basically a custom mailbox that delays the submission of new messages based on the mailbox size. Problem: it blocks the thread to achieve the delay, also it doesn’t seem to be used or maintained. 4)The TimerBasedThrottler makes our producer only create X amount of work per time unit, so it basically gives it a speed limit. Problem: how do you find out that number? You really want to go full speed if you can, but then you risk overflowing the mailbox. Systems behave differently in production under different load conditions, so this clearly isn’t a nice solution.

Work Pulling Pattern to the rescue!

The Work Pulling Pattern solves that exact problem, allows you to scale your system up and down dynamically during the execution and distribute work across the cluster to keep all your machines busy. And the overhead is minimal as you will see. In fact you can use the existing implementation from my github project, which also contains an example usage scenario.

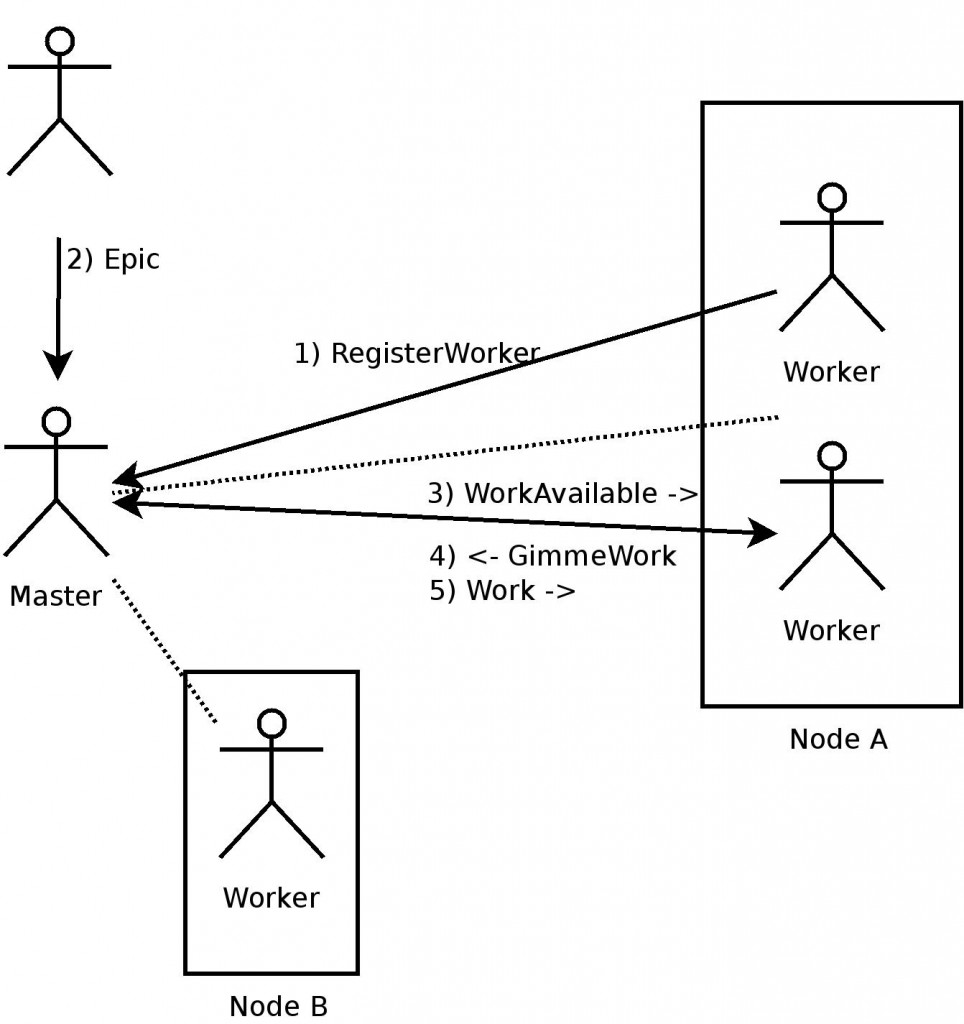

To get started you need one master and as many workers as you want. When a worker starts, it looks up the master by it’s actor path and registers itself. That means that you can add more workers on the fly (or remove them) which will immediately join into the party.

When a master receives a collection of work (we call it Epic) it notifies all workers by sending a broadcast message WorkAvailable. The workers then pull work, execute it and ask for more work. The cycle ends when there is no more work available, as the master simply doesn’t respond any more.

These are the guts of the worker:

def receive = {

case WorkAvailable ⇒ master ! GimmeWork

case Work(work: T) ⇒ doWork(work) onComplete { master ! GimmeWork }

}

def doWork(work: T): Future[_] //abstract, depends on what you want to do

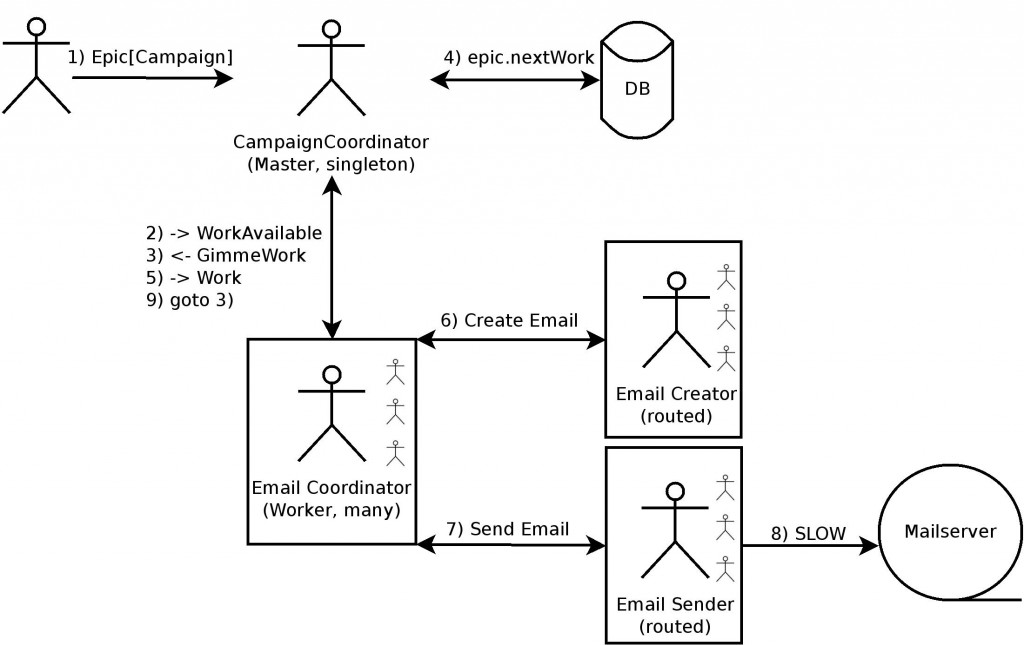

And this is all we need to implement the worker for our sample scenario. We send the context to the Email Creator, which responds with the complete email. We send that to the Email Sender, get some result back (e.g. a send report) and then our future completes, so that the worker automatically asks for more work. Easy, no?

def doWork(context: T): Future[_] =

for {

email ← creator ? context

result ← sender ? email

} yield result

//equivalent to:

def doWork(context: T): Future[_] =

creator ? context flatMap {sender ? _}

Benefits

1) No more out of memory issues because of too many messages in the mailboxes.

2) We only create as much work as is actually needed - Kanban style! This also means minimal liability for the workers. If a node goes down, we only loose the messages that were currently worked on.

3) Completely non-blocking, fully utilise your resources.

4) The actors involved can still receive other messages, e.g. to stop them.

5) Distribute work across the cluster with ease. Fully utilize all your boxes so you don’t need more than necessary.

6) Scale up and down dynamically by simply adding more nodes to the cluster during the execution of an epic. The workers on that node will happily join in with the other workers and start kicking off work to speed up the execution. Afterwards you can shut it down again to save some pesos. Cloud computing at it’s best!

7) It’s not a polling model where you have the overhead that workers regularly ask for work. They only ask when there’s actually work available.

8) Easy to use: simply instantiate a master, give it a name and implement doWork on the worker.

The complete picture

You’ve seen the implementation of the worker for the email sending scenario: all we needed is a short doWork block. The Campaign Coordinator is now the master node that distributes the work, but doesn’t need any other logic. The Epic knows how to get the next batch of work, I’ve left out the implementation here because it’s trivial. Imagine something like dao.findWorkBatch. And that’s it!

Getting started

All it takes is to instantiate a master node, give it a name, create an epic and obviously workers that implement doWork. Easy peasy. Have a look at the github project, which also contains an example usage scenario (WorkPullingPatternEmailScenarioSpec). Feel free to clone / fork / steal / pull-request / whatever it ;)

Credits

As mentioned before this is based on Derek Wyatt’s blog post. If you’re interested in Akka I highly recommend Derek Wyatt’s book Akka Concurrency - I’m just reading it for the second time ;)